Open-Source Software and Localization

An introduction to OSS and its impact on the language industry.

Published March 2005 in Multilingual

Computing & Technology.

By Frank

Bergmann

Open-source software (OSS) is already part of the mainstream information

technology. Most medium and large companies in the world are already

using it in some way or another. Apart from being cheaper, OSS is

considered to be more secure and more flexible than its commercial

counterparts. Corporate customers love the independence from a particular

software vendor and the possibility to customize the software to

the company’s needs, making it difficult for closed-software

providers to compete with OSS.

However, OSS just recently became the candidate for “the

next big thing” in the IT industry, the driver of a major

wave of change that might radically alter the market forces, comparable

only to the introduction of the PC or the Internet. But this time,

the revolution is not that much about technology, but about the

business models of the IT companies. This article explores some

of these potential changes and how they might affect localization

customers and providers.

The Rise of Open-Source Software

Before starting to discuss the impact of OSS on the software localization

process, we need to understand how OSS went from its roots to conquest

the corporate world. OSS was “born” in the 1960’s

and 1970’s in the university and research environment [1].

Researchers started to use computer programs for their activities

and, working in a non-competitive environment, began to share the

resulting computer programs amongst them just like they did with

their research findings. These groups of collaborating software

developers are today known as “open-source developer communities”.

However, these early OS developers wanted to make sure that they

received the fame and reputation as the authors of the code, similar

to the scientific system of quoting research publications. So the

“GNU Public License” (GPL) software license emerged

[2], implementing the scientific citation rule in the domain of

intellectual property rights. The GPL advocates that everybody can

use, modify and redistribute “GPLed” software, provided

that the initial authorship information is maintained. However,

modifications and additions to GPLed software are GPLed again, creating

what is known today as a “viral effect”. The GPL “infects”

other code when combined, so that the body of OSS grows and grows

ever since then.

OSS Leaves the Academic Niche

A major breakthrough for OSS came with the advent of the dot.com

boom. The Internet initially developed in research institutions,

and most of it is based on OSS. Also, the first industry-strength

versions of Linux appeared during this time, creating an ideal environment

for the young entrepreneurs. So it is no surprise that many startups

during the dot.com boom used the readily available OSS as a base

for their business. Google, eBay, Yahoo and Amazon are all still

using this infrastructure.

Another breakthrough came with the need of these first OSS companies

to support and maintain their software. So they started to outsource

these services to other companies, effectively creating a market

for the first Linux distribution companies such as RedHat and SuSE.

The business model of these companies is based on selling professional

services around the free OSS product.

The support work of these companies contributed to the quality

of the OSS, lifting it into the same quality dimension as its closed-source

competitors. And the availability of professional services made

OSS an attractive choice for companies of all sizes who had to slash

costs after the dot.com bust.

Finally, another important wave of change is just starting: OSS-based

companies have started to offer “mixed-source” [3] software,

extending OSS with proprietary functionality. These companies use

OSS merely as a base, while providing the same service level to

their customers as their closed-source competitors. As a result,

the marketing mussels of these companies now push OSS. The most

famous example in this field are IBM and Novell with their Linux

strategy and Sun Microsystems with its StarOffice/OpenOffice and

Java Desktop products.

The “Pure OSS” L10N Market

But how is the l10n market going to look like that is created

by these new players? To answer this question we are going to differentiate

between “pure” OSS and “mixed-source”.

Looking at the l10n needs of “pure” open-source developer

communities, we may find that these communities are not very attractive

customers, because they do not earn any revenues from their software

products. Instead, they have to rely on volunteers from within the

OS community in the same way as they rely on volunteers for software

development. The quality of these translations is in general not

as high as in closed-source software. However, this situation actually

stimulates unhappy users to participate in the OS project and to

contribute an improved translation.

However, there are some notable exceptions to this system, namely

when OSS customers are willing to pay for a professional l10n. In

particular, this is the case in the public sector where government

agencies around the world seem to favor OSS over proprietary software

[4,5]. There are bodies in the European Union facilitating these

efforts [6], so we may expect an increasing standardization in the

products being employed and a need for professional l10n.

The Mixed-Source L10N Market

The situation is more promising in the realm of mixed-source companies

who somehow combine OSS with proprietary software in order to deliver

a professional product to the market. These companies need to provide

high-quality l10ns and have a budget and an organization in place

to provide this service. For instance, Melissa Biggs from Sun Microsystems

Globalization Engineering Group reported to us in a telephone interview

that the “l10n processes for OpenOffice are basically the

same as for other Sun products”.

However, mixed-source companies can also rely on the l10n volunteers

from the OS community, depending on quality and completeness requirements

and the available budget. The Sun G11N Engineering groups for instance

has started a “Pilot Process” to “improve communication”

between the Sun g11n group and the OS community [7].

OSS L10N Technology

We are now turning our focus towards the technical resources and

skills that a l10n company needs in order to enter the OSS l10n

market. To shed some light in this area, we present you below the

l10n architectures of three very different OSS applications: Linux

is an operating system, OpenOffice is a desktop application similar

to Microsoft Office and ]project-open[ is a web-based application.

Also, the three systems are very different with respect to the

l10n organization, with Linux being a “pure” OSS and

localization by community volunteers, OpenOffice l10n management

split depending on the language (Sun manages 10 languages, the OS

community the rest) and ]project-open[ l10n split depending on application

modules.

Common to all three systems is that their l10n processes are considerably

different from the ones used for standard Windows applications.

Every system comes with its own set of l10n tools and philosophy,

requiring a considerable learning effort from a potential l10n provider.

Frank

Bergmann is a l10n consultant and

Frank

Bergmann is a l10n consultant and

founder of ]project-open[. He can be reached at

frank.bergmann@project_dash_open.com |

Conclusion

OSS l10n is probably not an interesting mainstream l10n market

yet, and pure OSS will probably never be. However, the overall share

of OSS is growing fast and mixed-source l10n will become an interesting

market in the close future.

Companies who are determined to enter this market will need considerable

in-house technology resources. Getting involved in a particular

OSS project may be a good start to investigating the new terrain.

Case Studies

Below we present three different open-source software packages

and compare the technical and linguistic aspects of their localization.

"Tux", the Linux Penguin. Linux

is probably

"Tux", the Linux Penguin. Linux

is probably

the most well known open-source product. |

Linux Localization

Linux [8] is probably the most well known open-source product.

Linux servers represent 15.6% of 2003 overall server market with

growth rates of 40% annually (IDC). Linux is currently localized

into some 73 languages.

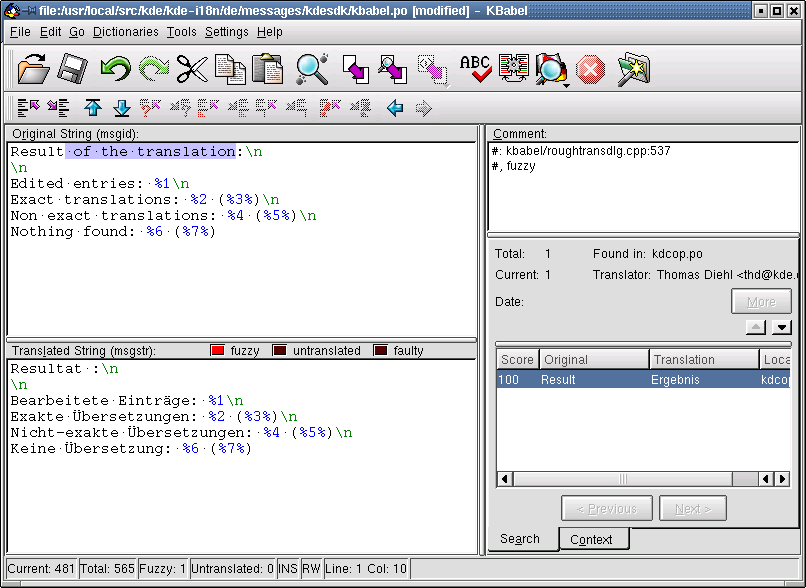

The Linux l10n software architecture is based on the GNU “gettext”

tool suite [9], together with a range of gettext compatible translator’s

tools such as KBabel [10], PO-Edit, GTranslator and others. Gettext

allows identifying translatable strings in the Linux source code

and extracting them into a format suitable for KBabel and the other

l10n tools. This l10n architecture is shared by the majority of

open-source projects, forming the de-facto standard in open-source

related l10n.

The quality requirements for the Linux operating system and server

software in general are considerably low, because most Linux users

are system administrators with a high level of English. Also, users

of open-source software typically don’t expect a very high

level of translation quality and completeness.

The l10n “market” of gettext is organized as groups

of volunteers from the target language countries. Most of these

volunteers are university students who are using the software for

their own purposes.

OpenOffice Localization

OpenOffice [11] is an open-source office suite similar to Microsoft

Office, including applications such as word processor, spreadsheet,

presentations and drawing. OpenOffice has been localized into 25

languages and has been downloaded by some 16 million+ users. OpenOffice

is an open-source variant of Sun Microsystems StarOffice product

and localized under the organizational umbrella of Sun.

The OpenOffice l10n architecture is similar to the GNU gettext

architecture explained above. A specific localization tool called

“localize.pl” [12] is used to extracts translatable

strings from the source code. This list can be converted into the

gettext format suitable for KBabel or into a format suitable for

Trados and other translation memories.

The l10n quality requirements for OpenOffice depend on each language.

OpenOffice inherits the professional l10n of the 10 languages under

the responsibility of Sun’s G11N Engineering Group (FIGS,

Swedish, Brazilian Portuguese, Japanese, Korean, Simplified and

Traditiona Chinese) [7]. Several open-source groups consisting of

volunteers handle the translation of the remaining languages.

OpenOffice is currently developing a “Localization Pilot

Process” [7] to involve the open-source community into the

l10n process, probably with the goal of cutting costs. This process

will reduce the need for professional l10n outsourcing if successful.

![]project-translation[ [12] is a web-based project management and workflow system specifically designed for translation and localization companies.](../../images/logos/logo.project-open.white.gif) ]project-translation[ is a web-based

]project-translation[ is a web-based

project management and workflow

system specifically designed for

translation and localization companies. |

]project-translation[ Localization

]project-translation[ [12] is a web-based project management and

workflow system specifically designed for translation and localization

companies. ]project-translation[ is “mixed source” software

because most of its modules are open-source, while a company provides

professional services and extension modules.

Being a typical web-based application, ]project-translation[s can

rely on a relational database to store its localization strings.

This organization allows ]project-translation[ to provide several

l10n tools via a web interface. In particular, it supports a “translation

mode” (see screenshots) that allows for online translations

within the application context, similar to the Catalyst and Passolo

resource editors.

The quality requirements for such a mixed-source web applications

are in line with industry standards.

Members of the open-source community are currently carrying out

most of the translation work of the OS modules. The l10n of the

closed-source modules is outsourced to professional translators.

Screenshots

The KBabel main translation screen.

Please click on the image to see the enlarged image.

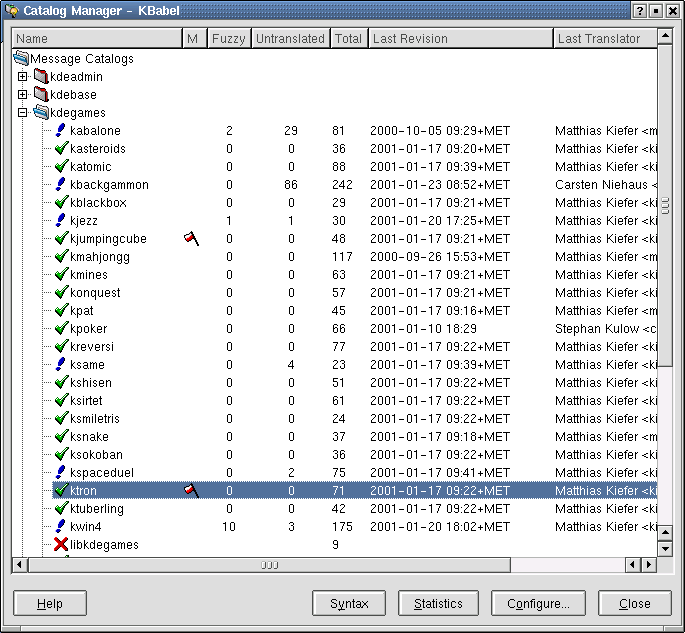

The KBabel Catalog Screen allows keeping up with translation in

large projects.

Please click on the image to see the enlarged image.

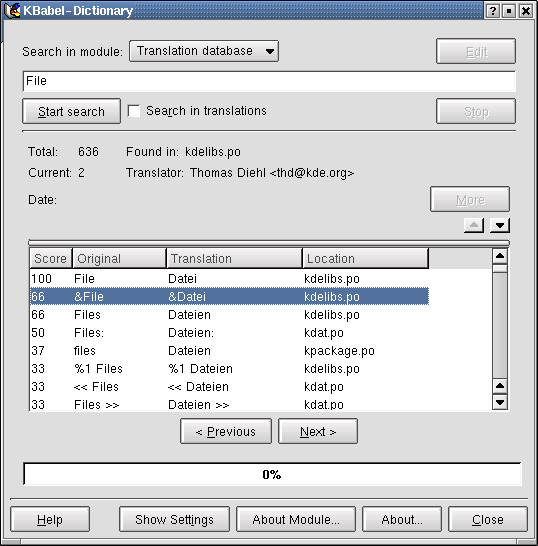

KBabel directory – basic terminology maintenance

Please click on the image to see the enlarged image.

An example screen from ]project-translation[.

The same screen again, but in translation mode.

Green dots appear behind all translatable strings, allowing the

translator to

work in the linguistic context of the application.

The ]project-open[ translation screen from the example above.

The ]project-open[ catalog screen, showing the list of all translations

in a specific module.

Please click on the image to see the enlarged image.

References & Resources

[1] “A Brief History of Free/Open Source Software Movement”

http://www.openknowledge.org/writing/open-source/scb/brief-open-source-history.html

[2] The GNU Public License

http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/gpl.html

[3] “Open, closed: Novell's 'mixed source' software”

http://star-techcentral.com/tech/story.asp?file=/2004/9/10/technology/8872977&sec=technology

[4] “Governments Mull Open-Source”

http://www.businessempowered.com/issues/2004/03/en/dept_shortcuts.shtml#opensource

[5] Open-Source and Government: The “FLOSS ” Final

Report

http://www.infonomics.nl/FLOSS/report/

[6] European Commission IDA Open Source Observatory

http://europa.eu.int/ida/en/chapter/452

[7] “OpenOffice Localization Pilot Process”

http://l10n.openoffice.org/localization/L10n_pilotprocess.html

[8] Linux Homepage

http://www.linux.org/

[9] The Gettext Localization Suite

http://www.gnu.org/software/gettext/manual/html_mono/gettext.html

[10] KBabel L10N Tool

http://i18n.kde.org/tools/kbabel/

[11] OpenOffice Homepage

http://www.openoffice.org/

[12] OpenOffice L10N Framework (“localize.pl”)

http://l10n.openoffice.org/L10N_Framework/iso_code_build2.html

[13] ]project-open[ Homepage

http://www.project-open.com/

|